Corporations and the wealthy (CAW) both have large amounts of money. And you might assume that, apart from the money, they have little in common.

One group consists of businesses with shareholders and directors, while the other comprises rich individuals.

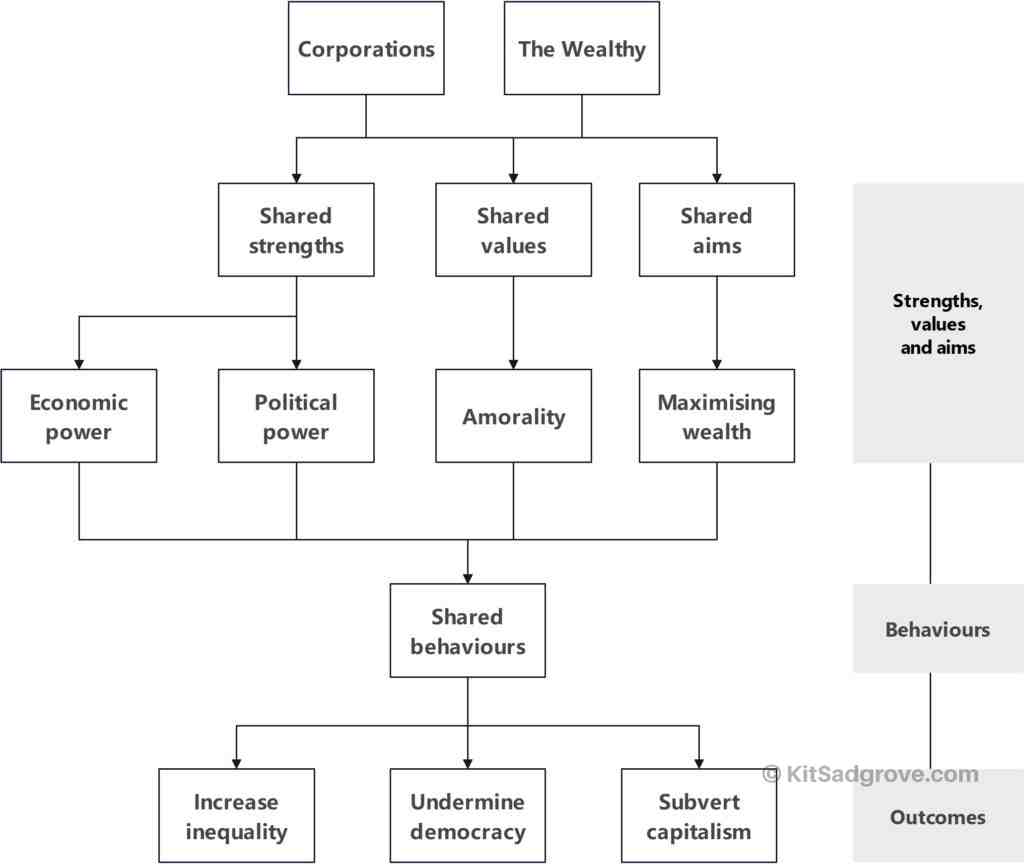

But as the chart below shows, they share a set of strengths, values, beliefs, needs and actions.

Talk to anyone at the top of a corporation, and you’ll find they have only one goal, which is to make profits. Although they preach about how they love their employees, and protect the environment, their real aim is to earn money for their shareholders and directors.

The wealthy share the corporations’ profit motive, but they differ in one other major respect – the wealthy have right-wing views.

That’s because they’re usually individuals, either self-made and therefore individualist, or else with inherited wealth. As other writers have shown, they tend to be anxious about losing their money, and protective of it. An analysis by the London School of Economics found that people who won on the National Lottery moved to the right((https://web.archive.org/web/20180702060908/https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/money-makes-people-right-wing-and-inegalitarian/)).

By contrast, corporate senior managers are usually less extreme, being subject to their shareholders.

Far-left politicians worry them slightly, because in government they seek to reduce the corporations’ power and profit. By contrast, right-wing politicians doesn’t bother corporations, because the right usually supports the needs of business and the wealthy.

Thus corporations and the wealthy thus share similar values and aims. Their priority is to protect and maximise their income, which leads to amorality: ethics doesn’t feature.

The two groups also have a set of shared strengths:

They have economic power. That’s to say, they have a lot of money in the bank which allows them to use others to achieve their aims and to buy advantage.

And having money gives them political clout. They have the ear of politicians and lawmakers and other influences.

This leads to a set of behaviours – specifically the hiring of the Concierge Class to cast a magic spell over their money, fix the world so it works in their favour, and push their message.

And over time the result is greater inequality, an undermining of democracy, and the subverting of ‘pure’ capitalism. We examine this proposition in more detail in the sections that follow.

Ideal capitalism, in the way that economists typically view it, is about perfect competition, where companies compete for your and my business. In practice, however, this rarely happens. Corporations prefer to have an easy life, as we all do. They’d rather buy up an irritating upstart competitor than slug it out with them in the marketplace.

Left to itself, capitalism leads to the survival of the most ruthless. And that’s why we have social democracy, which seeks to moderate the excesses of capitalism and provide the services that capitalists or the wealthy can’t on their own provide, such as an independent judiciary, the armed services and the police.

Corporations and the wealthy inevitably seek to promote their own views, and limit the ability of governments to support the rest of the population. That behaviour should come as no surprise. If you took any ordinary individual, and put them in a position where they were earning large sums of money, they’d instinctively seek to preserve and maximise their wealth.

And so we have a situation whereby corporations and the wealthy use their shared strengths, values and aims to increase their wealth.

Not all corporations are the same

It’s easy to think that corporations are all alike, controlled by the men and women in suits who turn up to the annual general meeting to vote. But it isn’t true.

Amazon is owned by one man, Jeff Bezos.

Meta, which is Facebook and Instagram, is owned by Mark Zuckerberg.

Microsoft belongs to Bill Gates. And so on.

And it’s not just the tech giants. Tata, the $4 billion steel company, is owned by Mr Tata. Elon Musk owns Tesla, the world’s 9th most valuable company.

Owning companies, properties and shares – that’s how the worlds of the rich and corporations mesh.

But some of the rich bosses don’t even own the business. One of the world’s highest paid execs is Michael Rapino, the CEO of Live Nation Entertainment. The business is owned by many investors, the largest of which is Vanguard, an investment management company. But Rapino’s lack of ownership doesn’t get in the way of his earnings, which stand at $139 million a year.

In other words, these organisations aren’t an amorphous mass. There’s a controlling brain behind each.

The same applies to the concierge class

Throughout the book I refer to bankers, not banks. I use the word accountants, not accountancy practices. And where possible, I talk about politicians, not governments.

It’s not always easy, because we can’t always pinpoint the individuals who made the policies or implemented them. But the point is valid.

I want to focus on the individuals, rather than the institutions. Every company and profession is comprised of individuals; and it’s the individuals who make the decisions and do the work. It’s the people in power who make the policies, and it’s the individuals at a lower level who willingly execute those policies. That’s why the members of the Concierge Class are important.